Following my previous three contributions regarding both the requirement to demonstrate increases in productivity and its potential impact on a workforce, I thought I would bring this theme to a close with some thoughts as to how this may link to the potential routes and twisting roads that we may be traveling down to get out of our current economic position of dithering around the edges of a full-blown recession.

After a tough spring, the economy returned to growth in the summer and early autumn – but only just. The slowest annual rate of expansion in almost a decade poses an obvious question: are you an optimist or pessimist?

Realistically, there’s not an awful lot to be optimistic about, even if you are an optimist. There were really only two pieces of good news for the government in the latest bulletin from the Office for National Statistics: the economy just avoided two consecutive quarters of negative activity – the technical definition of a recession – and there was a ‘bounceback’ in construction. Other than that, there was very little to put a smile on anyone’s face, especially those in charge of attempting to explain what was happening and putting a positive spin on the issues.

The growth in the third quarter was entirely down to a strong July. In August and September, the economy contracted. The problem with this is that, just like objects, economies build momentum as they travel through time, but at the moment it has been little momentum built going into the final quarter of the year.

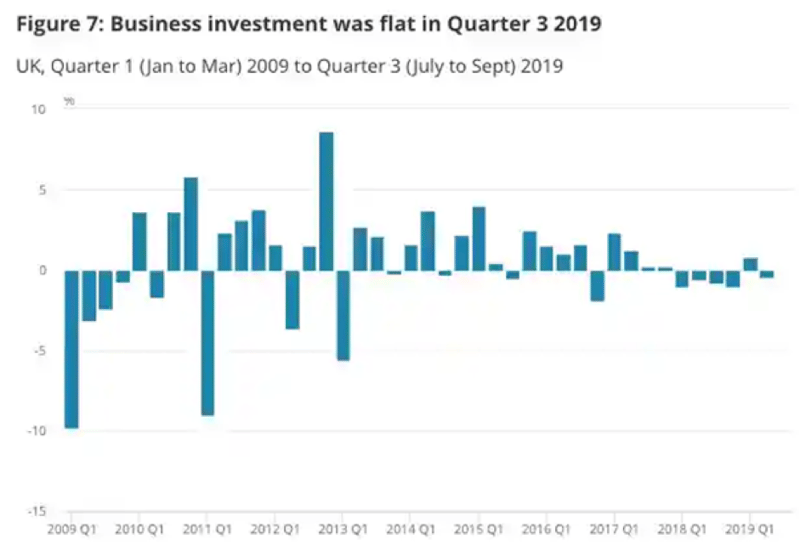

What’s more, the 0.3% expansion in the three months to September was heavily dependent on consumer spending. Business investment was flat over the quarter, as was manufacturing output, more than likely as a consequence of the uncertainty caused by Brexit, companies are nervous about committing to new capital projects at a time when there is so much uncertainty, with everyone sitting around a board table being questioned about every penny of spend.

Meanwhile, the slowing of global trade – in part because of rising protectionism caused by rising political nationalism – has made life more difficult for exporters in the UK to get their products into foreign markets. Unlike in the first three months of 2019, there appears to have been little stockpiling of goods in the run-up to the second missed deadline for Brexit, which could have flattered the third-quarter figures. More than likely because the original stockpile has not been used as Brexit was delayed again and again.

We should take little comfort from what was by UK standards a modest increase in household spending. While there’s no “feel-bad” factor as there was the last time Britain went to the polls in 2017, there’s not much evidence of a “feelgood” factor either.

There were fears expressed by some commentators that Brexit uncertainty might have pushed the economy into further negative growth but Britain’s services sector – which encompasses a range of industries from film and TV production to banking and the high street – performed strongly enough to push the UK into positive territory.

One of the long-established laws of economics is that business cycles never die, and there is plenty of historical evidence to support this.

- The Depression of the 1930s followed the collapse of a speculative bubble and was made worse by a series of policy blunders.

- In the mid-1970s, the long postwar boom was brought to an end by the sharp rise in the cost of oil.

- America’s deep recession of the early 1980s was induced by Paul Volcker who was installed as chairman of the Federal Reserve to beat inflation and did so by pushing up interest rates to cripplingly high levels.

- The slump of 2008-09 was a rerun of the 1930s only without the policy mistakes. Again, the trigger was a financial crisis that led to a sharp contraction of credit.

All of this makes the current state of the global economy particularly worrying because none of the usual explanations for a slowdown apply. Interest rates are not being hicked up. On the contrary, the big central banks are providing more stimulus. Nor are finance ministries sucking demand out of their economies through tax increases or public spending cuts. Oil prices are steady and there has been no collapse in house or share prices.

Russell Jones and John Llewellyn of Llewellyn Consulting, note: “The present situation is highly unusual. None of the negative shocks that customarily trigger a downturn are in evidence … and yet, the macroeconomic environment – never satisfactory at a global level since the 2008 financial and economic crisis – is souring.”

The IMF’s new managing director, Kristalina Georgieva has made clear, future forecasts are likely to make grim reading. The pace of global growth has been abating for the past two years. Manufacturing was first to feel the impact, but there have been signs recently that the malaise is starting to hit services. What’s more, growth is weakening pretty much everywhere. Georgieva calls it a synchronised slowdown.

So what is going on?

Theory number one is that this is simply a soft patch. If none of the usual causes of a recession are flashing red, then the obvious conclusion is that there is not going to be a recession.

Theory number two is that global growth is weakening because policymakers are using the wrong tools: too heavy a reliance on rock-bottom interest rates and quantitative easing, too little use of tax and spending. The IMF, which wants countries that have the scope to spend more freely on infrastructure and R&D, has some sympathy for this view.

Theory number three is that there are objective reasons why the global economy is heading for a recession but that they are not the usual ones. Protectionism is pushing globalisation into reverse; rising inequality has resulted in a dearth of demand despite a prolonged period of ultra-cheap money.

Theory number four cites the work of Nikolai Kondratiev, a Soviet economist who, in the 1920s said the world economy moved in long waves of 50 to 60 years, with an upswing driven by the arrival of a new technology and a downswing associated with its eventual eclipse. Periods of low growth come when the old technological paradigm is on its way out but has yet to be replaced by a new suite of innovations. If this view is right, the past decade will be seen as one such episode.

Theory number five is that the global economy – rather like a marathon runner in the last few miles of a race – has hit the wall. Growth, even the modest levels of growth seen over the past decade, can only be achieved through the accumulation of dangerous amounts of debt and a reckless disregard for the future of the planet. Seen from this perspective, it is not a question of hoping the fourth industrial revolution – artificial intelligence, genomics, robotics, the internet of things – will breathe new life into the existing model of capitalism. Instead, it means a complete rethink of the model from first principles. This is still some way off.

The initial response to the current slowdown has been to try a bit more monetary stimulus, even though central bankers such as Mario Draghi at the European Central Bank know it won’t really work. There comes a point when cutting interest rates is like pushing on a piece of string, and that moment has arrived.

Jones and Llewellyn suspect the next step will be monetary finance, which is where bonds are issued to pay for tax cuts and public investment, and the debt is then purchased by the country’s central bank. Crudely, the central bank prints money to pay for stimulus. It is known as “helicopter money” because governments dump large dollops of cash over their economies, hoping it gets spent on investment and activity to stimulate future growth.

This sort of approach has previously been shunned for fear that politicians will abandon all restraint and will keep spending until there is hyperinflation. Weimar Germany, Mugabe’s Zimbabwe and Maduro’s Venezuela are the recent examples of this, all of which ended up in both economic and social disasters. These situations occur where the usual political checks and balances are lost in the mess of weak and out of control opinions and ideas, either to the left or right of the center ground. Common sense is lost in the maze of media hype and the cult of personality. - Sound familiar?

Jones and Llewellyn say there are ways of countering the hyperinflation objection: for example that the extent of the stimulus could be legally limited to 3% of national output over two years. If ever there was a time to give helicopter money a whirl then this is it. Inflation is low, as are long-term interest rates despite high levels of government debt. Sooner or later, a government somewhere will be willing it give it a try.

The alternative to any or some of the above, or to be used with aspects of the above is that inward investment from the ‘Helicopter Money’ is used to stimulate productivity in a way that effectively means the individuals in the economy work their way out of the economic doldrums. This would also require social support to get more people into full-time work so as to spread the load that the effect of us all working harder would bring.

Issues also arise from this regarding the “feel-bad”/ “feel- good” factor. The prospect of working harder/leaner/smarter with the same amount or slightly increased set of resources for more than likely the same monthly return does not generate a “feel - good” factor for anyone and consequently spending and consumer confidence does not rise in line with the slight quarter on quarter rise in productivity. In fact, what tends to be felt is the opposite as the “feel - bad” feeling establishes itself for a while as the ‘economic lag’ effect works its way through the system. Money invested in public services such as hitting NHS waiting lists and school places takes time to hit the headlines. In the meantime, there is little incentive to be creative/entrepreneurial and work hard as you can’t see the fruits of your labors.

One final point to make is that with rising nationalistic tension, conflict (real or cyber) is always floating close to the surface. There is, of course, the economic cycle that always occurs as humans enter into conflict with each other, generating the urgent need for investment of public funds and kick-starting us all into action. A sobering but historically correct thought.

About Ascento

Ascento learning and development specialise in providing workforce development apprenticeship programmes to both apprenticeship levy paying employers and non levy employers. We work closely with employers to identify the key areas for development and design strategic solutions to tackle these with programmes that are tailored to each individual learner. With two schools of excellence focusing on Management and Digital Marketing we don’t deliver every qualification under the sun, but focus on what we know best and ensure that quality is at the heart of everything we do.