In my last blog called “Unprecedented times require realistic expectations of what the future may be like”, I commented on what our future economic recovery may look like and used the letters V, U and L as visual representations. I wrote this during the latter half and the beginning of the first week in April when predictions of infection rates, deaths and both the social and economic impacts were just that, predictions.

Since that Blog’s publication, I have been busy working with all my learners coaching and supporting them through their own professional issues within their work-based setting, whilst at the same time trying to keep myself up to date with the Govt’s ongoing attempts to deal with the consequences of the virus and then in some cases the unintended consequences of their actions/inactions. Throughout all of this, I have also been researching previous commentaries on the impact and recovery of such socioeconomic crisis in history. I have found little to cheer about.

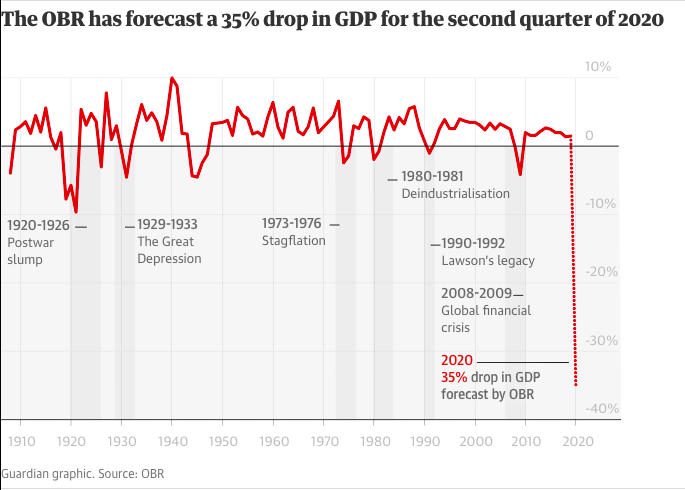

The Office For Budget Responsibility published data in the second week of April which was used in an article by Richard Partington https://www.theguardian.com/business/2020/apr/14/uk-economy-could-shrink-by-35-with-2m-job-losses-warns-obr?CMP

As you can see quite clearly it makes pretty grim reading in terms of where we are now compared to all cataclysmic and society-changing events in the 20th century. It was what economists call an exogenous shock: something that has a big impact but comes from outside the system itself.

I had initially thought that given the absolute cliff-edge drop off in Gross Domestic Product shown above, it would be more than reasonable to assume that our recovery out of the ‘Stay at Home’ policy and removal of our normal way of operating would be the V, with an almost immediate return to similar GDP levels with possible improvements as we work increasingly efficiently with new and improved ways of working enhanced by the crisis. However as the weeks have passed by, I believe this is an increasingly less likely proposition. At best it will be a U and even possibly now an L. That is unless a breakthrough in finding a vaccination or drug treatment is found quickly. If this is the case, now is the time for us to consider the longer and wider ‘recovery’ thinking, rather short term return to immediate profitability thinking that investors and markets so desperately crave.

A counter-argument to this as put forward by the IMF is that “the global economy is going to suffer its worst year since the Great Depression or the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility pencils in a slump unmatched for three centuries, that has absolutely nothing to do with the way the world economy is organised or run. Covid-19 does not mean the end of globalisation: it is a freak of nature, that’s all”. Unfortunately, the IMF does not have a great history of getting its predictions anywhere near correct. Their response to the 2008 crash is an example of this, where it considered that it was enough of a shock to the system to bring about fundamental changes to the operational activity of banks and other financial institutions. This never happened, with these institutions desperately trying to return to business as usual and succeeding.

The past 30 years have seen global markets – especially global financial markets – increase in both size and scope. Long and complicated supply chains have been constructed, with goods moving backwards and forwards across borders in the pursuit of efficiency gains; ‘hot’ money flowing into emerging markets looking for high returns and flowing out again just as quickly at the first sign of trouble. This is not and was not a stable bedrock on which to build sustainable economic activity. Then when an exogenous shock does occur it is unmanageable.

In response to this, some changes look inevitable. Companies will shorten their supply chains as a result of the disruption caused by the pandemic. Extra money will have to be found for health systems so that they can operate with more spare capacity than before in case there is a 2nd or even 3rd infection spike. Covid-19 has exposed the risks of a country such as ours in running down its domestic manufacturing base and relying so heavily on financial services. Investment bankers are surplus to requirements when the country is short of testing kits and PPE. Other reforms look tougher. There is a need for a stronger international system to both manage the fight against the pandemic and minimise the economic damage it has caused. No country can operate a go-it-alone.

Given this level of uncertainty and the likely levels of consumer confidence that always tracks the uncertainty curve, what as leaders of organisations can we do?

There are business models of dealing with uncertainty that are in place for the here and now, many of which use personal therapy models as their basis. I have adapted the five-step model below and used it many times in my own career to help me through some very challenging periods.

1. Replace expectations with plans. When you form expectations, you’re setting yourself up for disappointment. You can guide your tomorrow, but you can’t control the exact outcome. If you expect the worst, you’ll probably feel too negative and closed-minded to notice and seize opportunities. If you expect the best, you’ll create a vision that’s hard to live up to.

2. Prepare for different possibilities. The most difficult part of uncertainty is the inability to plan and feel in control. You need to plan for possibilities. Commit these to paper with notes and explanations to yourself, so as to reduce the stress and burden of trying to hold them all in your head.

3. Become a feeling observer. It isn’t the uncertainty that bothers many leaders, it is the levels of personal anxiety that it brings because we all speculate about our futures. As Leaders, we need to remind ourselves that we can’t possibly predict the future, but we can help create possibilities as in number 2 above.

4. Get confident about your coping and adapting skills. This isn’t the same as “expect the worst.” It’s more about assuring yourself that you can handle any difficulty that might come.

5. Focus on what you can control. Too often we overlook the little things we can do to make life easier while obsessing about the big things we can’t do.

These five processes when employed collectively by an organisation’s leaders can be very powerful in overcoming and reducing what too often are anxiety lead plans in response to a crisis and really do work in preventing some auto belief system responses.

Whatever the future does hold, our ability to manage the here the and now, whilst at the same time leading on shaping and envisioning the future it what is most important. Economic modelling for future expectations has never been able to truly capture the spirit of survival that we have always shown when are backs are against the wall. The only thing certain in economic modelling is uncertainty and so far, no amount number crunching using behavioural science data aligned to historic economic data will be able to predict what will emerge from this crisis or how long it will take.